As an IB student, you’ve probably seen it first-hand. There stands a student who was once just as incompetent, not-proficient, has-no-idea-what-they-were-doing as you. But in front of you, stands that student, speaking in (what seems like) perfect, native-sounding Japanese.

The power of ‘compound-learning’

‘Compound learning‘ is – as the name suggests – a method of learning I started doing early on in my language learning journey. It involves not solely focusing on one element of a language (i.e. speaking, listening, grammar, vocab, etc), but rather the entire language as a whole.

A common mistake I find most of my students and peers makeing is focusing wholeheartedly on one type of exam because “I’m fine with ‘listening’, I just suck at ‘reading’, so I’ll just focus on that”. It’s an interesting way-of-thinking if you ask me.

For example, allow me to use the overly used example of ‘how baby’s learn languages‘, after all it is the age at which most, if not all, of us pick up our first language. Many people argue that immersion is the best way to quickly learn a language.

However, I am personally not a fan of this model, simply because WE ARE NOT BABIES. But this fact puts us at an advantage. After all, I don’t see no baby using google translate, or even a dictionary for that matter of fact.

But the principle remains the same: a baby does not choose what KIND of language they consume, but rather they consume EVERYTHING and make connections between them all. Ok, enough with the analogy, let me show you what I mean.

Some background about the Japanese Language

(Feel free to skip to the next section if you are a seasoned learner).

The Japanese language is constituted of three scripts: Hiragana 平仮名, Katakana 片仮名, and Kanji 漢字. In the average piece of text you will find all three scripts used.

Hiragana is a phonetic alphabetic used to express all Japanese words as well as readings for Kanji (Chinese characters). Katakana is mainly (but not strictly) used to write foreign words, foreign names, and some onomatopoeia. Kanji are Chinese characters derived from traditional Chinese and are used to write some or parts of Japanese words.

It is important to note that many Kanji characters have several ways of reading them depending on the context. These are split into Japanese readings 訓読み(くんよみ)and Chinese readings (音読み).

So, as a Japanese language learner, you are expected to know how to read and write in Hiragana and Katakana and be able to use some basic Kanji. But HOW?

Compound-learning for Japanese-learners

This section outlines a method for compound-learning that I found particularly helpful for myself to create a solid foundation and kickstart high proficiency in my linguistic skills.

In theory, it is quite simple:

Firstly, find a new word. Often, this is plentiful in most of your language-learning journey. Then, turn, to your trusty dictionary and ask away (I like to use the app ‘Japanese’ on iOS; not sponsored).

Most dictionaries should provide the following (for kanji): meaning, readings, example sentences and common compounds. We want to take advantage of all of these.

If there is a kanji associated with this new word, take note of the stroke order and different readings. You don’t need to commit this to memory just yet.

Next, find the common compounds and note how the readings are used. There are rules associated with 音読み and 訓読み (which I recommend you check out), however, due to the vast number of exceptions, I found this way to be most effective.

After this, find some example sentences. I would grab a pen and jot these down. Try to translate these sentences by yourself before checking the dictionary’s version. If you are a more advanced learner, try writing the other kanji used in the sentence by yourself before looking.

From this process, you should find some problems:

a) idk some words/kanji used in this sentence

b) idk the grammar used in this sentence

c) idk anything in this sentence (except my word) lol

This is great!

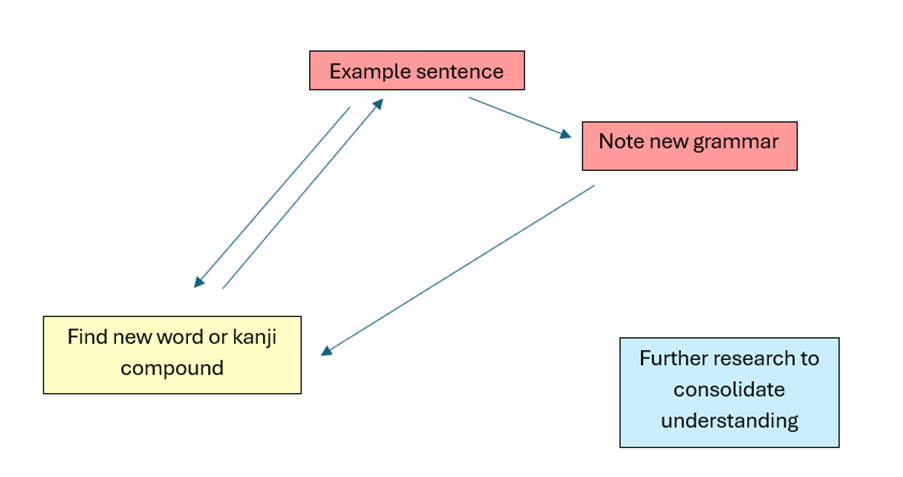

Your next step to compound-learning is to use these elements to learn even more, leading to an endless cycle of realising just how little you know (just kidding it’s not all that solemn).

The takeaway

The effectiveness of this strategy comes from the fact that we study the parts of a language by learning from the whole. Yes, you can try to memorise 200 vocabularies with flashcards, or dig through your textbooks and route-learn grammar, or strengthen the antagonistic muscles of your hand be rewriting kanji (all things I would recommend in addition to this technique, especially for beginners, sorry). However, you must be careful not to fall into the trap of structure.

If you don’t already know, your teachers DO NOT know everything. Neither do your tutors, or YouTube Sensei’s or university-level professors. Of course, neither do I. This is why you must explore this massive jungle that is ‘language’.

Picture this. I drop you miles away on a deserted Island with the bare essentials but not wifi connection. I can tell you the name of this island (Japanese) and the fact that there are trees, grass, killer monkeys, friendly mokeys, poisonous lakes and fresh water all day long. But if you don’t go in and experience those things for yourself you won’t know which is which.

Just like the scientific method, be curious, learn from the whole, and check if your understanding is correct. Use the vocab, grammar patterns and kanji you learn from compound-learning and ask for feedback from your teachers, tutor and friends (who have just a little bit more experience).

To conclude, using the compound-learning technique will improve your knowledge of the language. Whether you become proficient (then fluent) depends on your ability to use this knowledge, so ensure you practice what you learnt (i.e. handing in homework to your teachers, practising conversing, or even just writing to yourself).

Remember, everyone can learn, the question is are you willing to?

Best of luck,

J